For many years now, Friedrich Moser's documentary focus has been on the worldwide web. What once seemed to connect us all

has now developed into a diffuse space where doubts and wedges are driven into societies in an increasingly targeted manner.

HOW TO BUILD A TRUTH ENGINE addresses the issues of disinformation as a weapon, the call for a new journalism and the urgent need for democratic societies

to find a mode of coexistence inside and outside the net.

Were you prompted to address the theme of information warfare by progressive disturbing developments in the media or a very

specific occasion?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: The first impetus came from my desire to continue my work on cybersecurity, surveillance and counterterrorism after A Good American (2015) for cinema and Terrorjagd im Netz (2017) for Arte. For the TV documentary, I accompanied a Viennese start-up that developed software which enabled them to

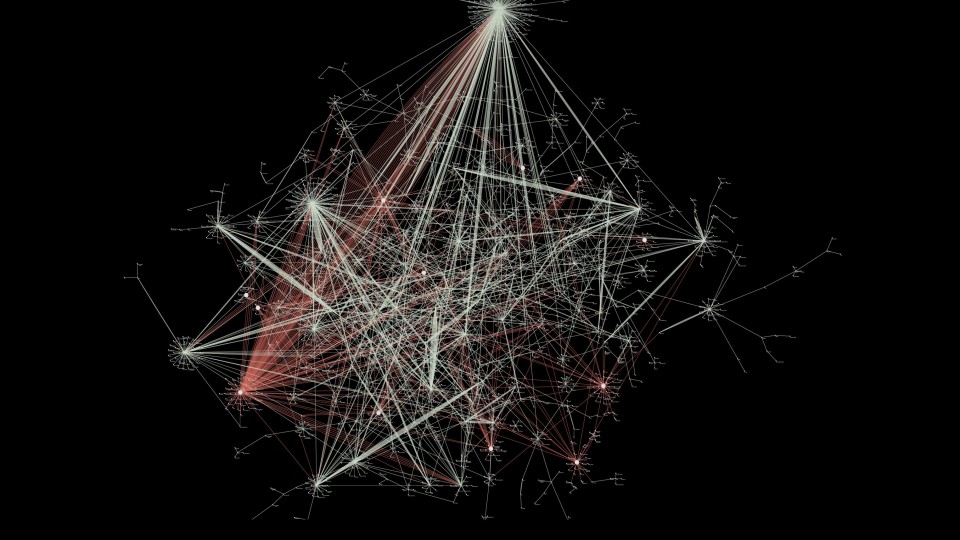

locate the support network of IS in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. One of the founders of the Viennese start-up, Jan van

Oort, began working in 2018 on AI software that would be able to analyse texts to determine whether they are real or fake.

At the same time, I heard about a European research project that was heading in the same direction. From that point onwards

I was waiting to see if I could make a documentary out of it all.

When did the concrete occasion for the film project arise?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: At the beginning of 2019, I received an invitation to a Hack-The-News Datathon via a mailing list. The aim of this datathon – a kind of data analysis marathon – was to develop software within

a week, in competition with various other research teams, that would be able to distinguish real news from fake news. I felt

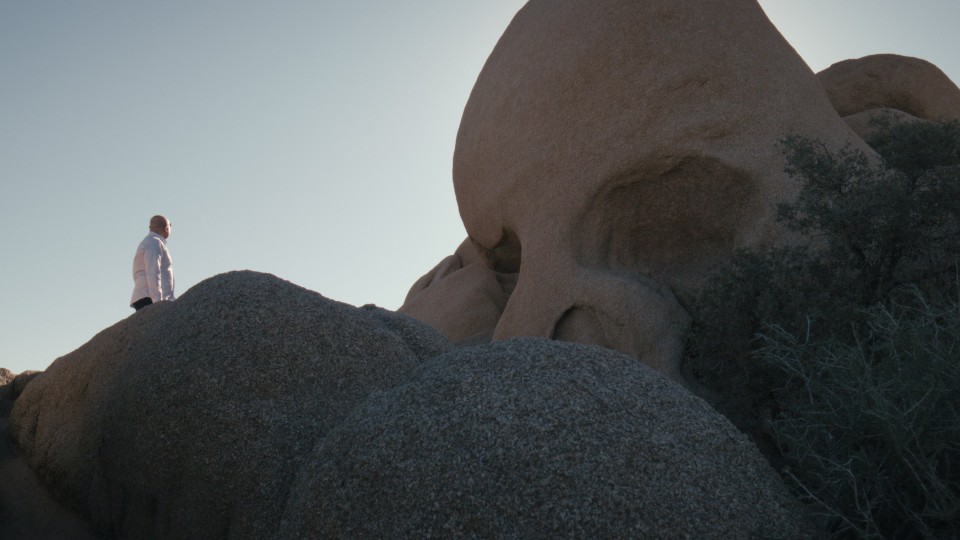

straight away that I wanted to capture that on camera, and I already had my first protagonist: Peter Cochrane, former Chief

Technology Officer of British Telecom. I also got the title of the film from him: How to Build a Truth Engine? was the title

of a presentation where he promoted the idea of automated fact-checking to stem the flood of lies and fake news on social

media. It quickly became clear that a purely technological focus would be too dry. So I integrated investigative journalism

as a counter-model to fake news. In late 2019/early 2020, we filmed in Washington DC and at the NYT. It quickly became clear

to me that what was being done there by the Visual Investigations Unit was journalism of a different calibre. Assisted by

evaluations from satellites, mobile phone data and private and public surveillance cameras, this team uncovers crimes against

humanity and top-secret smuggling operations. We came back to Vienna thrilled after the shoot, only to be met with terrible

news: our protagonist Jan van Oort had disappeared without a trace. Two months later, we learned that he had succumbed to

a heart attack in Peru.

How did the film gain new momentum after that?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: We realized that we had to start again. In the fall of 2020, I started researching anti-fake news software, and I came across

researchers from the University of Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of California, Berkeley, who had developed software

that allowed them to detect conspiracy theories. I had found my new story. The two researchers, Tim Tangherlini and Vwani

Roychowdhury, also brought neuroscientist Zahra Aghajan on board, and she in turn contacted brain surgeon Itzhak Fried. After

talking to everyone, I realized that software alone would not solve the problem of disinformation. We also need to know how

people’s brains process information.

So your research led you back to the USA?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: When the film began to develop a more American angle, I started looking for US partners as well. This involved financing on

the one hand, but I also wanted an executive producer, someone who would either make a major contribution to the financing

or significantly facilitate the marketing of the film by making their name available. For HOW TO BUILD A TRUTH ENGINE, George

Clooney was at the top of my wish list.

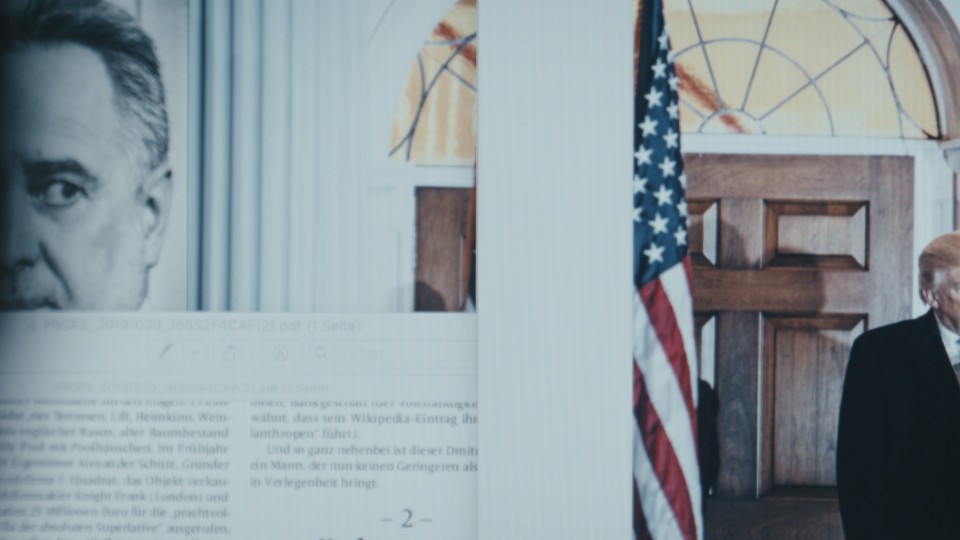

To what extent has George Clooney adopted a position on this issue?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: George Clooney was my first choice for several reasons. He studied journalism. Clooney's father was a news anchor. And George

Clooney funded a research program at Harvard that focused on the analysis of satellite data to investigate war crimes. Together

with his wife Amal, a well-known human rights lawyer, Clooney watched a 25-minute video and confirmed in a subsequent Zoom

call that he felt the theme relating to journalism and the images of the satellite evaluation were convincing. He has lent

his name to us as an executive producer, and he and his partner at Smokehouse Pictures, Grant Heslov, are helping us sell

and market the film.

Your project has changed a lot. Isn't the constant transformation an inherent element of the theme? How does a theme like

this become tangible at all, considering the current pace of developments?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: The technology may change, but the mechanisms remain the same. The techniques of disinformation in operation today existed

back in ancient China and among the ancient Greeks. I was less interested in the details of specific events, because they

are interchangeable; whether it’s Russian war criminals in Ukraine, Hamas terrorists or the QAnon followers who stormed the

Capitol, they all went through similar processes. I'm interested in these mechanisms, how and why disinformation takes hold

in our brains, and ultimately, how ordinary people become cold-blooded perpetrators, mass murderers who commit genocide. The

really tragic thing is that the very abilities which make our brain this incredibly wonderful organ also make it insanely

vulnerable. Our brains can be "hacked". And that happens by hacking the flow of information.

Peter Cochrane begins by mentioning the various spheres of warfare. Why do we move so quickly to war terminology in a documentary

about information and truth?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: Because information is being instrumentalized: on the one hand, in advertising and PR. And since the Internet has eliminated

the traditional role of the media as a "spam filter" for information in circulation, limitless opportunities to unleash unfiltered

information garbage on users have opened up. People get involved in vehement Twitter debates without even knowing whether

the other person is a human or a robot. Twitter is extreme, but this point relates to all platforms. There is a war going

on. When false information is unleashed on us, it doesn’t happen by chance. Information is a tool for gaining, maintaining

and defending power. It's about confusing people in such a way that they distrust real information.

Where have you found new ways and insights into how journalism can continue to fulfil its important role?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: In 2023, there was a conference in Vienna on journalism in the age of AI. We’re already at a stage where 60% of all Bloomberg

news today is compiled by bots, because they are faster at capturing and processing economic data. I believe technology will

open up a huge number of ways to relieve the burden of traditional journalistic work; journalists will be able to focus on

content. The NYT's Visual Investigations Unit has never had to retract or add to a publication. For me, precise work like

this, supported by technology, is "next level journalism". It's no longer a matter of how fast you are. The machines will

win that race; that's what they're there for. The journalism of the future will consist of guaranteeing authenticity, organizing

material and conveying it to people. Curating news rather than producing it.

One important finding made by brain researchers is that we learn based on responses to our actions. If, as is the case on

the net, you can spew out insults without any consequences, you’ll do that again and again. That’s what leads to brutalization

on the net. And it only benefits those people who are waging this information war; it drives wedges into society.

How did you develop a visual language for this complex content?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: Cinema involves capturing vast expanses or getting really close. I was faced with the question of how to describe activities

that largely take place in front of computers without having to show screens all the time. So I added metaphorical layers.

To illustrate the acceleration of the transfer of knowledge from the European Middle Ages to the present day, I filmed in

Kremsmünster Abbey Library. Perhaps it’s good to see old manuscripts and appreciate what a painstaking process it was to codify

content. To be aware of who had access to knowledge and how rapidly that’s changed in today's world. Our brains are not made

for the abundance and speed of information that we have today.

What is your hope for a "truth engine"?

FRIEDRICH MOSER: I think my film is a wake-up call. The truth engine consists of three components:

1. Media forms that function as spam filters; they need to be updated to meet the information flows of the 21st century.

2. We will need more software to organize, process and sort out information. The onus is on politicians to invest more in

these technologies. The question is whether politicians, who now produce their own news and distribute it unfiltered, would

be interested. But for the wellbeing of society, for the health of discourses in a society where compromises must necessarily

be found, these filters are needed; the truth is needed.

3. It's up to us. We need to be aware of how vulnerable we are. Instead of reacting impulsively to information, we must first

consider why someone is writing or saying something. As media consumers, we have the task of performing a reality check!

And then there must be framework conditions: social media must be regulated in the same way as traditional media. If it were,

a lot of this lying would come to an end. Automatically. After all, there are consequences in your private life if you lie.

Maybe we also have to learn to deal with an imperfect world, with an imperfect self. Scaling back the way we interact with

each other to times before the invention of the Internet or Instagram. Just getting back to normal. I grew up in a community

of 1500 people. Everyone talked to everyone else, regardless of their political affiliation. We have to get back to that place.

Move out of our bubbles. Everybody needs to talk to everybody. Nobody is perfect, and you always learn something. Even if

it takes the form of questions being raised that you hadn’t posed before.